UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

It is estimated that there is around half a million Croatians, and their descendants, living in the United States of America. This immigration began back in the 16th century, when sailors from Dubrovnik crashed onto the coast of North Carolina, and melded with the native Roanoke tribe, which led to the creation of the Croatan tribe; a tribe of nearly white natives. During his visit to the tribe, Governor John White found the word ‘Croatan’ carved into a tree. There is a Croatian Indian Park on Roanoke Island, as well as a Croatian Island, which got its name in 1858, and the Croatian National Forest.[1]

The picture on the left was made by Governor White, and shows a native village belonging to the Roanoke tribe, from around 1585. The picture on the right shows a map from 1599, which has the Croatan gulf listed on it[2] (both photos courtesy of Adam Eterovich).

The governor near the tree with the word ‘Croatan’ written on it, from 1590

However, the first big wave of immigration began in the second half of the 18th century, which reached its peak in 1910. This was when Croatians from the north of the country started arriving in Pennsylvania, and then New York, where they worked in factories, while Dalmatians flock to California, and people from Pelješac gather in Louisiana and the rest of the inlands. Croatians largely congregated in the larger cities, such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Pittsburg, Cleveland, and others.

The next wave of immigration took place between the two wars. After World War II, the reasons people left their homeland were both economic and political. Immigrating to America is still common today, and can again be referred to as economic emigration.

Some Croatians in America have received significant accolades for their professional achievements.

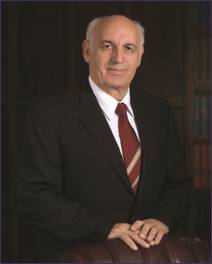

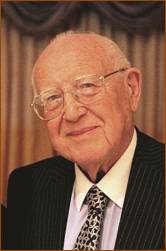

Dr. Luka Milas was born in Zmijavci, in 1939, and obtained his medical degree in Zagreb, in 1963. He spent a time working at the Ruđer Bošković Institute at the Biology Department, and the Central Institute for Tumors in Zagreb. He went to Houston’s University of Texas to complete his post-doctoral studies, at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, at the Department of Experimental Radiation Oncology, where he worked until 1969. After a while of living in between Zagreb and Houston, he permanently moved to the USA in 1980. At M. D. Anderson he became the head of the Department of Experimental Radiation Oncology. Luka Milas is a member of the Croatian Academy of Arts and Sciences, and he received a gold medal from the American society for therapeutic radiology and oncology in 2004, as a reward for his dedicated work in exploring the basic biology of tumors and the efficiency of clinical radiation oncology.[3]

Dr. Luka Milas (photos courtesy of the Milas family)

Croatians in America also were also notable in various combat situations across wars in Korea, Vietnam, and World War II.

Peter Tomich, born in Prolog, near Vrgorac, in 1893, was a World War II hero. His name was originally Petar Herceg, and he had the family nickname Tonić, which later on became the family name Tomić. He arrived in America in 1913, and joined the army. After World War I, he moved to the navy, where he served as the chief engineer on the destroyer Utah. The start of World War II caught him in Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii, when the Japanese attacked the USA in 1941. Tomich kept the engines of a ship that had been hit by two torpedoes running until most of the crew could abandon ship. All of this went on under the fire of Japanese aircraft. The ship listed, and Tomich made the crew leave, while he controlled the pressure building up in the engines, in order to stop them from exploding, as that would have killed everyone near the ship. Despite his efforts, Tomich and another 58 members of the crew (of 1001) were ultimately left trapped on the ship, not far off the coast.

The remains of the listing destroyer, the Utah, still loom next to Ford Island. A memorial was placed alongside it, along with a plate recalling Tomich’s heroic actions. The plate was placed as part of the commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the attack, during which senator Frank G. Moss remarked that he hoped there would come a time that memorial plates would no longer be reserved for those fallen in battle, but for those who live in peace. During the event, divers placed an urn bearing Tomich’s remains into the wreckage of the ship, as it had been everything to him; home and family.

Pearl Harbor, view of the memorial for the fallen crew of the Utah, where the memorial plate for Petar Tomich resides

Remains of the destroyer Utah

Memorial plate for Peter Tomich

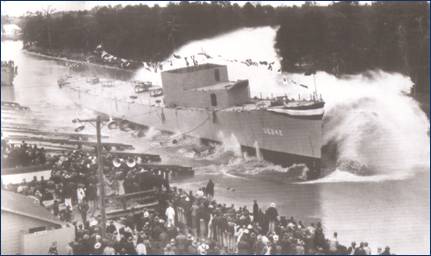

A year after his death, in December 1942, at the Brown Shipbuilding shipyard in Houston, the USS Tomich was launched, in honor of the late Tomich. It served in the American navy for 30 years, after which it was removed from the registry, and scrapped in 1974.

The launch of the USS Tomich at the shipyard in Houston (photo courtesy of Vladimir Novak)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to posthumously honor Tomich with the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Tomich’s medal

In 1989, in Newport, Rhode Island, the navy built a museum, school, and dorm for the Naval Academy there, and named it Tomich Hall. His medal was on display there for many years, as Tomich’s family could not be reached. It took time for his actual family name to be uncovered. The medal was ultimately given to his family on May 18th, 2006, during the stay of the US aircraft carrier Enterprise in Split’s harbor.

Another Croatian had a decorated career as a soldier and marine; Colonel Ivan Slavich, born in San Francisco, in 1927. His father was a court official, and politically active as a democrat, while his grandfather was a barrel maker from Croatia. Slavich took part in World War II, as well as the wars in Korea and Vietnam. He was the commander of the first wartime helicopter unit in the military history of America. He was the bearer of 16 commendations, and was known as Drivin’ Ivan. He died in Florida, in 2012.

Ivan Slavich (1927 – 2012) and his commendations

(photo courtesy of V. Novak):

Ivan Slavich (1927 – 2012) and his commendations

(photo courtesy of V. Novak):

![]() Legion of Merit with Two Oak Leaf Clusters

Legion of Merit with Two Oak Leaf Clusters

![]() Air

Medal with Four Oak Leaf Clusters

Air

Medal with Four Oak Leaf Clusters

![]() Army Commendation Medal with

One Oak Leaf Cluster

Army Commendation Medal with

One Oak Leaf Cluster

![]() National Defense Service Medal with

One Oak Leaf Cluster

National Defense Service Medal with

One Oak Leaf Cluster

![]() Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

Armed Forces Expeditionary Medal

![]() United Nations Service Medal for Korea

United Nations Service Medal for Korea

Croatians are also present in the movie industry. Actor and producer, Branko Lustig, was born in Osijek, in 1932. Lustig’s family is Jewish in origin, and had suffered several losses in World War II, and Lustig himself was an Auschwitz survivor. From 1955, he worked in Jadran film, where he started his career. He worked on the notable post-war movie Ne okreći se sine, which won three awards at the Pula Film Festival. In 1987, Lustig moved to America, where he enjoyed extraordinary success. He became the first and only Croatian to receive two Oscar Academy Awards for his work as a producer. He won the first Oscar in 1994, for the movie Schindler’s list, and the second in 2001, for Gladiator. Along with the other producers of Schindler’s list, he founded the USC Shoah Foundation in 1994, which gathered accounts from around 52,000 individuals, from 61 countries, who had survived the Holocaust, so that their stories would never be forgotten.

Branko Lustig (photo from Public Domain)

Three producers of Croatian descent have received an Emmy television award, for excellence in the field of TV production.

Brenda Brkušić Milinković was born in Chicago, in 1981. Her mother is Dianna Ukas, from Jezera in Murter, and her father is Kruno Brkušić, from Bogomolje on Hvar. As a student for KOCE-TV, Brenda recorded, produced, and wrote the script for a movie title Freedom from Despair. She is the bearer of multiple awards, among them the CINE Golden Eagle and a commendation from Congress for promoting human rights through her work. She has received four Emmys for her work. The first was for the movie Bloody Thursday, and the second for the show The Hollywood Reporter in Focus: The Wolf of Wall Street. She received the last two Emmys in 2015; one for the movie Actors on Actors, and the other for Mia, A Dancer’s Journey, a movie about the ballerina Mia Salevnska. Brenda Brkušić’s husband is Mike Milinkovic, originally from Lika.

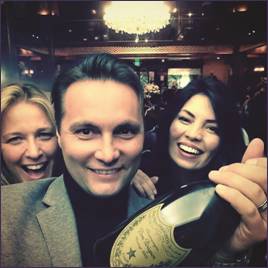

Kruno, Brenda and Dianna Brkušić, at Brenda’s wedding, and Brenda with her husband, Mike Milinkovic.

Boško Bobby Grubić was born in Sisak, in 1972. An actor, director, and producer, he lived in London, and then Nashville, where he studied mass communication. He settled down in California, and cooperated with Steven Spielberg at Universal Studios. After that, he became the executive producer for all TV ads for the American International Group. He is the winner of three Emmys. He is the first Croatian producer/director to win an Emmy for achievements in TV production. He won his first Emmy as a student in Nashville, in 1999. He won the second in 2006, and the third in 2007. Bobby Grubić is a humanitarian whom both Croatia and his hometown of Sisak can count on.

Bobby Grubić

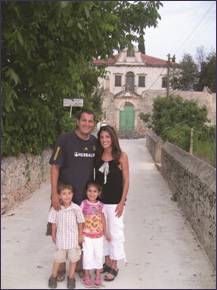

Jack Baric is yet another Emmy winner, for his work on the movie Bloody Thursday, which focuses on dock workers in the time of the Great Depression. Baric is the author of numerous documentaries, among which is Searching for a Storm, which covers the Croatian Civil War and the case of general Ante Gotovina. Baric’s movie, A City Divided, on the rivalry of college soccer clubs in Los Angeles, was used for a campaign to raise money to fight cancer, and ultimately helped raised $600,000. Jack Baric was born in San Pedro, in 1964, and is proud of his Croatia heritage. His mother, Anđelka, is from Veli Rat on Dugi Otok, and his father, Lenko, from Sutomišćica on Ugljan. Baric’s wife, Denice, is partly Croatian as well.

Denice and Jack Baric at the Emmy Awards, and with their children in Sutomišćica on Ugljan

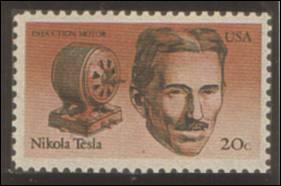

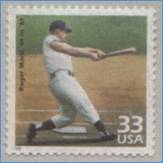

The US post office has dedicated post stamps to two Croatians. One was printed in honor of Nikola Tesla, and the other for Roger Maris.

Nikola Tesla was born in the Smiljan village near Gospić, in 1856, and died in New York, in 1943. He was one of the greatest inventors of all time. He achieved all of his greatest accomplishments in the field of electrical engineering. In 1895, the first power plant on the Niagara River was built according to one of his ideas. He submitted around 700 various patents. The unit for magnetic induction is name after him (T), thus effectively immortalizing him.

The Tesla Motors company was founded in San Carlos, California, and it manufactures electric cars.

Post stamp and Tesla Motors pump in Los Angeles (photo courtesy of Bobby Grubić)

Roger Eugene Maris was born in Hibbing, Minnesota, in 1934, to a family of Croatian immigrants of the Maras family, from Karlobag/Pag. Both his grandmother and grandfather, on his mother’s side, came from Croatia. Roger, who changed his last name to Maris, became an American baseball legend. Playing for the New York Yankees in 1961, he became the first player to beat the record set by Babe Ruth, 37 years before. He scored 61 home runs in the ‘61 season. American Croatians were delighted to learn of this baseballs stars’ Croatian heritage. Maris died in 1985. A post stamp with his likeness was published in 1999, titled Roger Maris, 61 in ’61.[4]

[1] Eterovich, Adam. 2003. Croatia and Croatians and the Lost Colony (1585- 1950). Ragusan Press. San Carlos, California. Pg. 88.

[2] See 32, pg. 86. (photos courtesy of Adam Eterovich)

[3] Kukavica, Vesna. 2004. Onkologu Luki Milasu američko priznanje. Slobodna Dalmacija. 29. XII..

[4] Courtesy of John Kraljich, from New York.