NAVARINO

Navarino Island is located to the south of the Land of Fire, on the Chilean side of Beagle Canal, opposite Ushuaia, the southernmost city in the world. Navarino also contains the southernmost settlements in the world; Puerto Williams with around 2,000 citizens, and Puerto Toro even further south, with but eight families, members of the Chilean police and naval force, living there. Several localities on the island bear Croatian names, such as Puerto Beban and the Caleta Beban caves, located in Bahia Windhond, which were named after Fortunato Beban from Ushuaia. The mountain on the western side of the island, which is 642 meters tall, is called Monte Vrsalovic. It was named after Antonio Vrsalovic (1869-1938), from Povlja. Next to it, at a height of 650 meters, is the Paso Mladineo mountain pass, named after Antonio Mladineo. At the Lennox island Vrsalovic has found enough gold to buy a farm. Together with Luis Mladineo he started to grow sheep in 1896 in Wulaia bay. They already had 4 000 sheep next year, but Mladineo died. He was inherited by his brother Antonio who became partner to Vrsalovic.

The picture on the left shows the western side of Navarino Island, where Monte Vrsalovic and Paso Mladineo are located. The picture on the right shows the shallows of Bahia Windhond, where Puerto Beban and Caleta Beban are located.

Monte Vrsalovic is on the west on the picture, and Caleta Beban is to the south, in Bahia Windhond. In the photo on the right, there is Vrsalovic family: Antonio and his wife Natalija Mladineo, their daughter Juanita and son Jose Miguel.

Navarino Island is the home of the native Yagan tribe, who were the southernmost people on Earth. They were, as they are no longer around. They would often walk around naked, entirely adapted to the harsh climate, cover themselves in grease from sea-dwelling animals, and dive in the sea, which only ever reaches a high of nine degrees Celsius. This was the case until the arrival of white people, who brought over foreign viruses and bacteria, which the natives had no resistances to. They clothed them, and introduced them to alcohol.

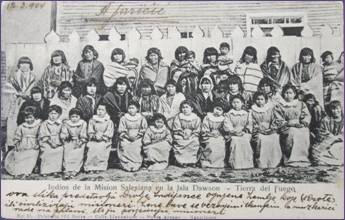

Salesian missionaries came over from Europe, and they were granted a 20 year concession by the Chilean government to educate and assimilate the natives on Dawson Island in the Magellan Strait to the north, some thirty hours away from Navarino using ships available at the time. This was where they deported all the natives from the Land of Fire and the southern islands, split among two missions, which were more akin to detention camps that provided them with food and shelter. This was effectively a continuation of the genocide that the colonists had started. The population on Dawson Island was very mixed; the Selkínam that hadnít been killed off by farmers, the Yagans, and several other tribes, none of whom shared the same language. A letter from Nikola Bandić from Punta Arenas in 1895, addressed to Juraj Kapić, editor of Splitís Pučki List (Folk Magazine), had the following to say about how the white people treated the natives:

They brought over 164 wild natives from the Land of Fire (Terra di Fuoco) to Punta Arenas. Among them were children, men, middle-age people, and 80 young women. These poor kids were naked and barefoot, and the ice is harsh. They make for a sad sight, freezing, their dark skin trembling from the cold. People brought them clothes and coats out of pity, and the Yagans resorted to eating shoes out of hunger. When we saw it, we rushed to get them food, but their masters beat them with switches and herded them into a giant house, like cattle. This is where they would toss them raw, lean meat, which the savages would tear apart like wolves. Your heart would break hearing the wails of a poor native woman, roaring like a lion, when they took and sold her child, accompanied by the haunting cries of a father for his lost son, a sister for her brother, and so on. Please, have this printed in Pučki List, because I know that Dalmatians laborers would want to know.

In 1904, my grandfather, Ante Bezić, received several postcards at his home in Split, sent by Andrija Juričić, founder of Domovina (Homeland) magazine from Punta Arenas, featuring images of Dawson Island. He wrote: A village in the Land of Fire (the islandís territory was part of the Land of Fire), where the natives are being civilized.

Another postcard from Juričić, from the same place, specifically said that the missionaries were taming the wild natives, which shows that they considered them animals. That Dawson Island wasnít a suitable place to live is only further enforced by the fact that, many years later, Chilean president Augusto Pinochet (who was in power from 1973 until 1990) banished his opponents there. Thus Dawson Island became known as Pinochetís infamous prison.

Few managed to escape the detention camps, and yet, there are no more natives around today; no Selkínam, no Alacalufe, and no more pureblood Yagan. The last pureblood member of that tribe was Rosa Yagan Miličić (1903-1983), or Lakutaia le Kipa in her native tongue, éena iz uvale kormorana (Woman from cormorant bay). Their names were given to them based on where they were born: lakuta means cormorant, aia means bay, and kipa is woman.

On the left is Lakutaia le Kipa, Rosa Miličić, in 1917, near a village in Mejillones bay, on her home island of Navarino. The picture on the right is from 1978, near the Ukika village in Puerto Williams, where there are people with native blood living today (photos from the book Rosa Yagan, El ultimo eslabon, by Patricia ätambuk).

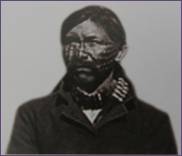

Rosa got the Miličić family name when she married. Her husband was Jose Miličić, the last chief of the Yagan tribe. His native name was Lanamutekensh. His mother died when he was four. His father gave him up for adoption to Ante Miličić of Brač, who had a concession on Nuevo Island, under the condition that he would attend high school in Punta Arenas. After finishing school, Jose returned to Nuevo, and raised sheep with his stepfather. A yearly naval report said that their estate, which had some 600 sheep, was very suitable to live in. Jose married, had children, and ended up a widower. When he met Rosa, he was living with his son, and was quite a bit older than her. He immediately won over the young beauty, and he had the support of her mother and the other women, who used to say that it was good when a man is older, as heíll no longer waste his time on silly pursuits, and will instead take care of his wife and canoe. And so it was. Since Jose was educated, the tribe chose him for their leader and judge in the village of Mejillones. As judge, it was his job to keep the peace and civil behaviour in the tribe. Jose and Rosa didnít have children, but they raised his son from his first marriage. Rosa outlived Jose, and after his death, she stayed with a man from Chiloe.[1] Women didnít have any options at the time, and had to get by in this manner.

Jose Miličić (1886-1961), the last chief of the Yagan tribe (from Patricia ätambukís book)

![]()

Spear tip which belonged to Jose Miličić (authorís private collection)

Navarino Island, Robalo bay, where the natives gathered seashells.

Rosa passed away in 1983, in the native village of Ukika, at the edge of Puerto Williams, where all of the Yagan were moved to from Mejillones bay in 1967. There is a still a native graveyard there. Cristina Calderon, the last half-white half-native, lives in Rosaís house, the best kept in Ukika today, and is the only person who still speaks the native language of the Yagan.

Chilean author Patricia ätambuk interviewed Rosa Miličić in 1975. She published this important accounting in her book Rosa Yagan, El ultimo eslabon, for which she was accepted into the Chilean Language Academy.

The author with Cristina Calderon, the last person of half-white/half-native heritage, in front of the renovated house of Rosa Miličić in Ukika.

Ukika village today; view of the Beagle canal and the Argentinean coast across the way, along with Gable Island.