EUROPE

According to conventional views stemming from the not-so-distant eighties of the last century, Croatians weren't considered immigrants in other European countries. They were workers, living abroad until their jobs were done, however, nowadays the second and third generations of their offspring still live there. With the fall of Yugoslavia, even more Croatians have left their homeland, and all of them are considered to be Croatians living abroad today.

Wars always created new borders, and thus it was after World War I that we lost Boka kotorska, which was a part of Dalmatia up until then. This portion of the Dalmatian populace became citizens of a different nation, still living in the same place. Looking for traces of Croatia in Boka kotorska makes no sense, because it is all Croatian anyway, according to Tripo Schubert from the Croatian Civic Society of Monte Negro, Kotor, in reply to my inquiries on the matter. Similar examples can be found in other locations in our immediate vicinity.

AUSTRIA

The bulk of the population of Croatian descent in Austria can be found in the eastern section of the country, in Gradišće or Burgenland, which stretches all the way into Hungary and Slovakia. In the 16th century, fleeing from the Turks, this area was inhabited by Croatians from Lika, Gorski Kotar, Slavonia, Banovina, Kordun and western Bosnia. Given that Turkish rule over these areas lasted a long time, the Croatians that moved to these areas integrated into their new environments and remained there. Thanks to their strong sense of national identity, they continued to call themselves Croatians, and they even managed to preserve their language, which was based on the Chakavian dialect. Up until World War I, there were bilingual schools in these areas, which were subsequently close down. The Austrian state limited the use of Croatian in public life for a long time, only to reinstate it in six out of seven of Gradišće’s districts in 1987. Thus we can find bilingual signs in many areas in Gradišće today.

In 1929, in order to preserve their national and cultural identity, Burgenland Croats founded the Croatian Cultural Society, with its headquarters in Eisenstadt or Željezno today. The Austrian post chose to honor the society in 2009, when they published a stamp in honor of its 80th anniversary[1].

However, this is not the only post stamp in Austria dedicated to Croatians. One of them features the character of Paula von Preradović (Vienna, 1887-1951), the granddaughter of Croatian poet and writer Petar Preradović (1818-1872). Paula was a writer, like her grandfather, and she wrote of the beauty of the Adriatic Sea, as she felt a strong connection to the homeland of her ancestors. In World War II, she aided the resistance movement, and was hunted by the Nazi regime. She is also known as the author of the lyrics used in the Austrian national anthem today[2].

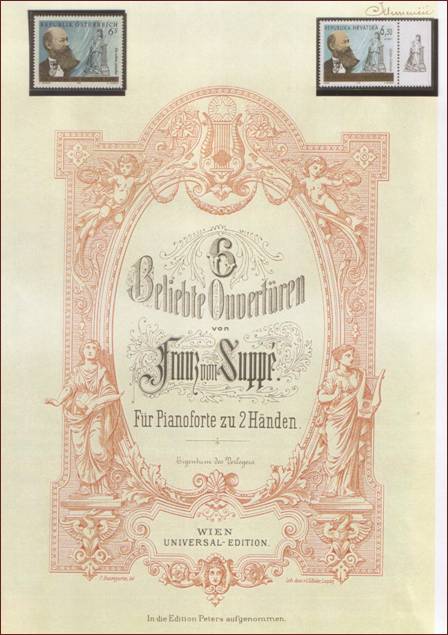

Composer Franz von Suppé (Split, 1819-1895), who had spent his childhood in Split and Zadar, also obtained his own post stamp in Austria. He had acquired his musical education at a very young age, and thus started to compose music. Even though he studied medicine in Padua, he remained faithful to his music. After his father’s death, he moved to Vienna along with his mother, where he studied composing and conducting. He maintained contact with Dalmatia throughout his life, and frequently visited Split, Šibenik and Zadar. He would incorporate Dalmatian folk music in his works, and the titles of his pieces were related to our names, such as Missa Dalmatica for example[3].

In the church of St. Andrew in Graz, there is a memorial plaque dedicated to Ivan Antun Zrinski (Ozalj, 1651 – Graz, 1703), the only son of Petar Zrinksi and Katarina Frankopan. It was commissioned by the ‘Brothers of the Croatian Dragon’ society in 1944, when the remains of Ivan Antun Zrinski were moved to the cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Zagreb. Zrinski acquired his higher education in Vienna, and spoke seven foreign languages. Even though he was loyal to the king, he was under constant surveillance due to his family history, and so it was after some twenty years spent in dungeons that he died of pneumonia in Graz. With his death, the long line of the great Zrinski family was ended.

Graz, the church of St. Andrew and the memorial plaque dedicated to Ivan Antun (by virtue of the Lukić family from Graz)

In Linz, the third largest city in Austria, located in the northern region, there is a Croatian street, or ‘Kroatengasse’ in German.